A little over two weeks ago, I deleted the Instagram app from my phone. Since then, I have circled back to completing a long-abandoned book and subsequently cracked open two others (Imitation Democracy and writings on post-Soviet cinema)—after which, I sprinkled in some seed-planting for a mini herb garden during my work week, replenished a sourdough starter, and printed an overdue document. Needless to say, the last two weeks have given me much to reflect on. And yes, I can already hear the prognosis through the screen (no, this will not be an entry about internal migration or “escapism” in the face of authoritarianism)…

It isn't the first time I’ve left for some stretch of time. My longest period of insta-sobriety was about three months and took place between January 2021 and March 2021. When I re-emerged back into the digi-sphere, I surprised friends with the first serious relationship of my early twenties alongside some new paintings. “Checking out” of the digital then was, in some ways, a natural response to the global pandemic. Typically, this meant temporarily deactivating my account for some arbitrary period of time until I could healthily return (which isn’t entirely unrelated to what I am doing in this case, but that is beside the point). I also learned that Instagram has insidiously programmed their app to recognize when user activity is suddenly halted. For example, when you deactivate your account, they will send you an email about a week or so later saying that “Your password has been changed” or that there are “(Blank #) New Direct Messages awaiting your response”—despite knowing that your account has been purposely placed on pause.

It was during this first departure that I also managed to read the book This Is Your Brain on Birth Control by Dr. Sarah Hill. In her years-long efforts, Dr. Hill studied how hormones (whether ingested, injected, or inserted) change the way neurons and chemicals respond or reorganize within your body and brain. Although the book itself was not entirely intersectional in its participants or the application of hormonal birth controls beyond cis-gendered women, I found the most distinct takeaway from her studies to be that individuals who decided to quit taking the pill after many years experienced a meaningful change in their attraction to a partner or respective romantic interests. Crazy how your hormones can literally shape your preferences. But this point is only tangentially related, as it elucidated the larger concerns of what effects my brain on Instagram had on my body.

Having reinstated this digital abstinence again now, I noticed the ripples in my mental cognition almost immediately. In the first few days, I’d instinctively lift my phone to scroll to the screen where the app I was looking for was no longer there. This would then segue into a reshuffling of various media apps—none of which could ultimately satisfy a @ nolitadirtbag cringe post or the high of the infinite scroll. I knew there was nothing there for me to look at, yet even as I became accustomed to my dead-end wallscreen, I'd still pick up my phone to look at something.

What was I looking for?

Who was I looking for?

Who was I looking to see was looking at me?

Where and how does social media impede on our personal lives or relationships? That seems to always be the question, and why is it that we inevitably return to this technological stonewalling?

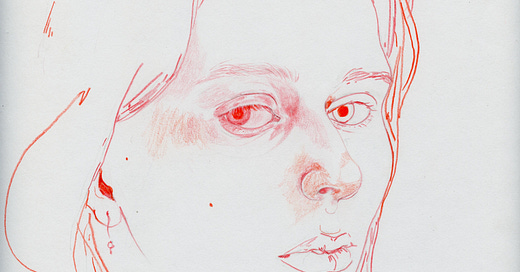

This is by no means a brilliant observation, and I most certainly will not be the last person to cave—but it is becoming increasingly difficult to accept that any of it is normal. Your brain on Instagram is not normal. Frighteningly, I don’t even recall how or when exactly my brain became so reliant on this interface for meaningful communication, for defining humor amongst my closest friends, or to hear about long-anticipated exhibitions for friends of friends, war, political upheaval, etc. For that matter, when did having a “digital presence” become integral to building a relationship with an art audience, collectors, or prospective gallerists, or, or, or—

Living cannot be virtual, and now more than ever I’ve found myself flying too close to the sun. More pressingly, we cannot afford to tune out from relevant happenings, injustices, or the political destabilization that is afoot in our democracy—as our awareness of the erosion of privacy, international humanitarianism, or legislative infractions of inalienable rights has far greater consequences than ever before. Especially given that this kind of erosion has historically and systemically targeted the fatigued, overworked, underpaid, and marginalized who are too often already stretched thin.

Slowly, I think I am steadying my navigation— my desperate attempt to recover an understanding of the day, a sense of distance, and of urgency. That my need to live and respond to the real world must become sturdier than the pull of amalgamated images, comment threads, video sequences, and obtuse signals of interest.