In my previous substack essay, I very briefly alluded to the unspoken expectation placed on artists to imagine or conjure up new images. Some painters feel this sentiment is completely irrelevant to their production or acceleration as an image-maker, while others (on the extreme end of the conversation), feel particularly sensitive to the use of images within their work, especially in the case of online or existing images. The hard rule amongst these kinds of painters is that artists who rely on images to create paintings, are perhaps “missing the most crucial case for painting.” Take from that what you will.

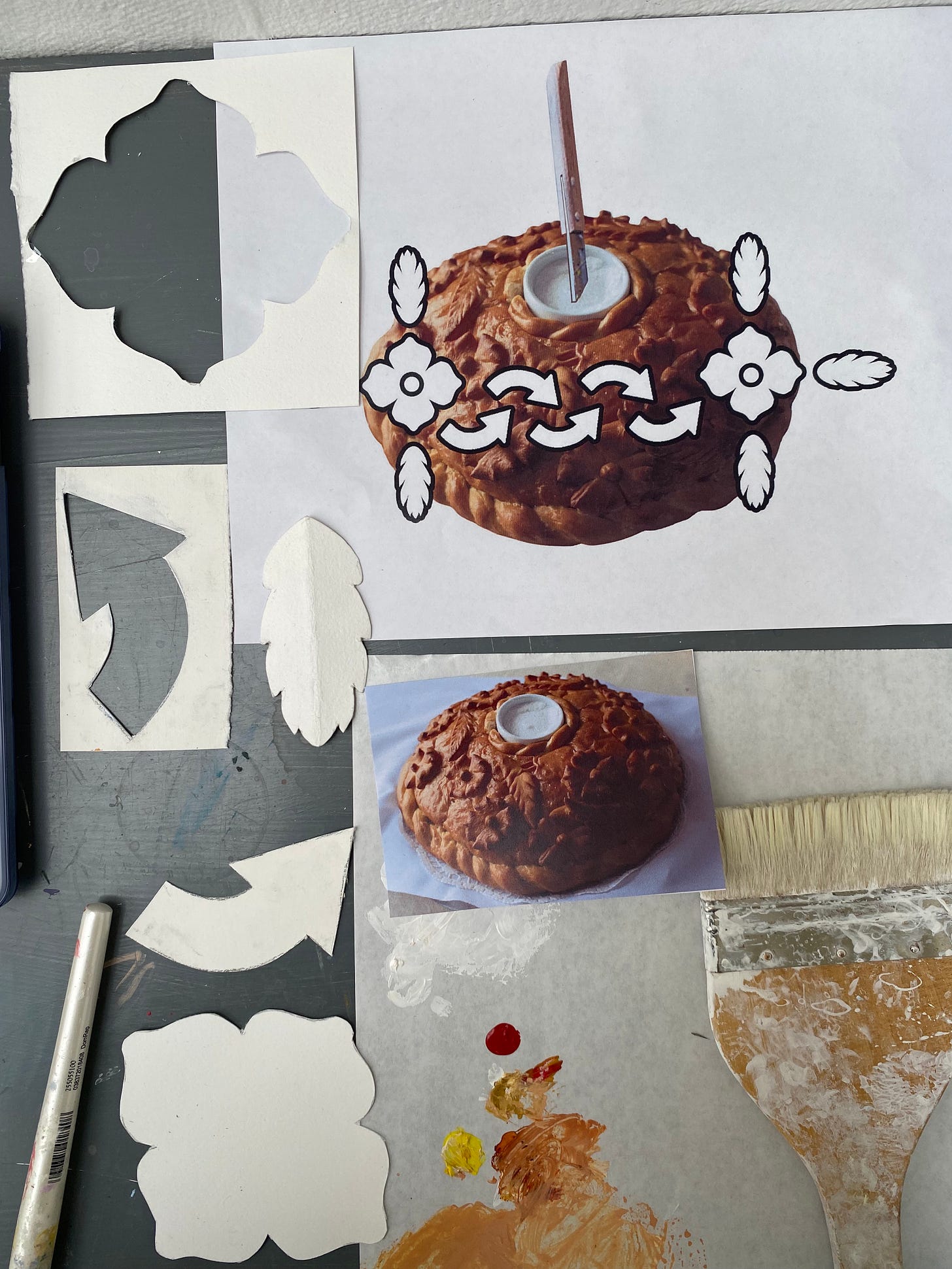

I belong to the category of painters who collect and reference images all the time. More often than not, I start by sifting through images. Heaps and piles of them. The exciting moment that transforms painting for me is that the array of collected images may not necessarily appear within a given work. Perhaps it is a texture, a small mark or divot, a hue that generates an idea for a new work—the most delectable moments in image-making can be found in images that are totally illegible, far too pixelated to retrieve any information from. What kind of paintings can then emerge through such perceptive constraints?

Likewise, the integrity of an image, whether it be online or in real life, does not disqualify its use in my works. To paint, is to translate— and let me tell you, almost everything can be translated.

Oxford languages define translation as the following: 1.) to express the sense of the (word or text) in another language, 2.) to move from one place or condition to another.

The latter instance describes a kind of physical metamorphosis that is more relevant to the conversation of painting. Interestingly enough, there is a brief verbal incongruence that at times may surface in live or academic linguistic translation. Not all words can be direct formal translations because some do not have an equivalent in the second language, therefore the next most comparable option must be used in its place. A favorite example of this is the Russian idiom ‘у него крыша поехала’— meaning ‘his roof is riding away’ (used to remark on someone’s ludicrous rationale or abhorrent decision-making). Its direct translation serves no cultural purpose to an English language setting. Language aside, painting ultimately takes on a slower pace and permits a controlled environment, but it rarely will ever produce direct or nearly perfect interpretations. In some sense, that is the most obvious intention of painting: the promise of a direct but different transcription (albeit, there are some alarmingly similar works out there).

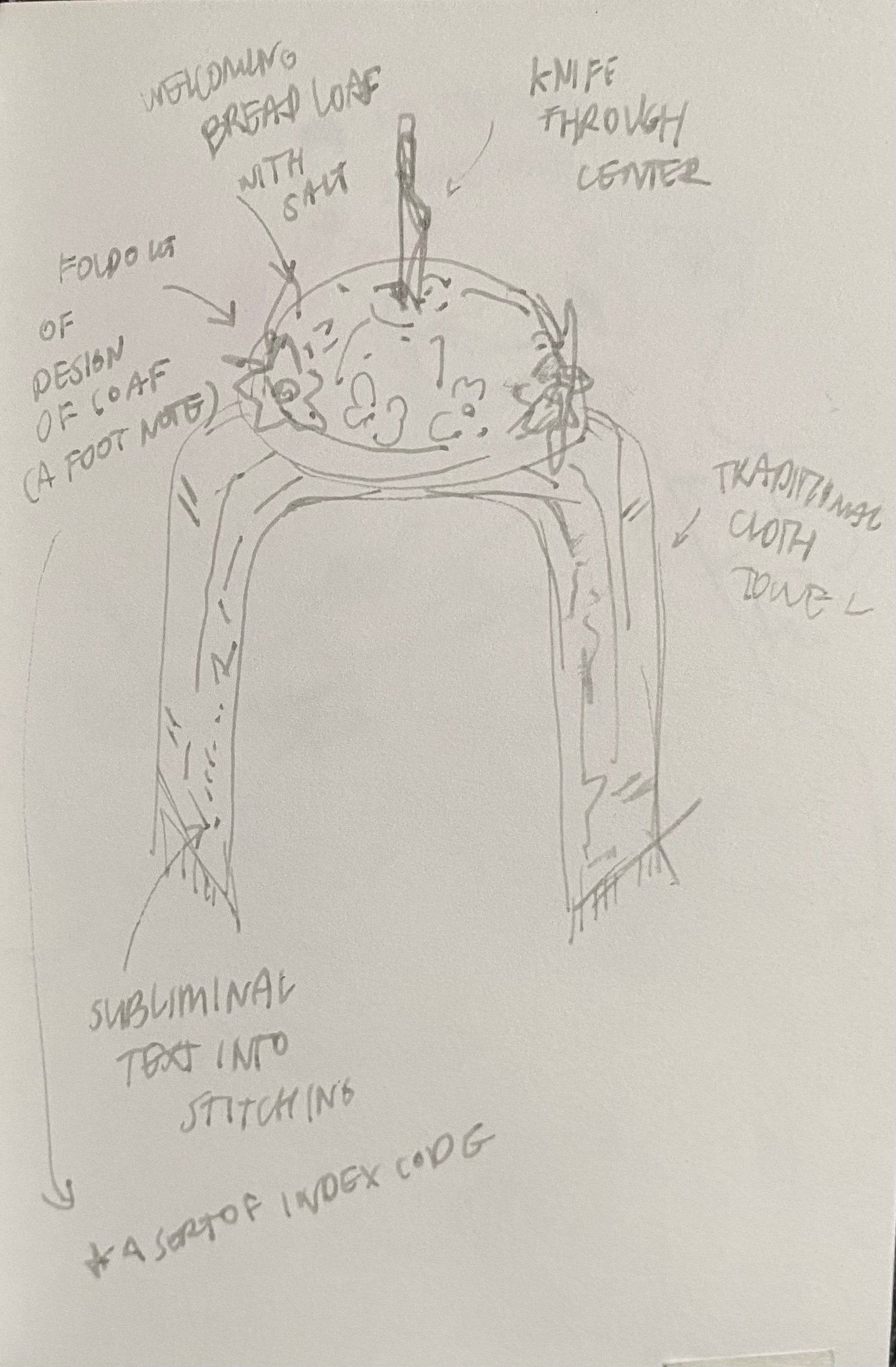

When preparing to embark on a new work, I recognize that I am also not the kind of lawless painter who selects something without then considering its use on a more introspective level. Where is the image from? Who is pictured in the image? How or at what moment was this image conceived? For what reason?—does it even matter? Alongside these questions, and a slew of other aesthetic judgements, the use of images finally assists in my arrival at a destination for new image-making. Although I will not be revealing exactly what throngs of the internet or the world I go to in search of these images (at least not in this essay), I wanted to share a few spreads from my sketchbook to unveil how in this feverish search for images, I produce very few sketches that later guide me in my painting process.

All of this “looking at images”, only to produce no sketchbook work!?

Believe me, I too feel the need to bonk myself over the head for this!

But for transparency and an honest “glimpse into the process”, I must divulge that sketchbook work, particularly when used to brainstorm compositions and various arrangements, has never appealed to me as an arena for exploration in my image-making practice. In fact, I kind of hate it. I hate the process of sketching things, how inconsequential and half-hazard it feels. I’ve never been a fan of maintaining a “sketchbook” or producing “sketchbook art”. Without spiraling too far away now, the sketchbook has most beneficially served me as a record for references, notes, spiritual observations and working thoughts. The sketchbooks I keep today are methodically stuffed with things I find on the floor or tokens collected from new sites. They are almost exclusively filled with writing.

To close this reflection on the stages leading up to art-making, Ruth Asawa’s sketchbook works featured in her solo exhibition “Ruth Asawa Through Line”, last September at the Whitney Museum, served as a beautiful reminder of the triumphant observations that can be made when adequately maintaining this preparational art-making practice. In most instances though, I still tend to gravitate towards the ephemera retrieved from sketchbooks rather than the sketchbooks themselves. Perhaps you’ve noticed these materials displayed on a glass-enclosed table when walking through a museum exhibition. Next time, be sure to take a closer peek at those items, as more often than not they reveal something about the artist that cannot be gleaned from the operation of pen-to-paper alone.

Here are just a few “sketches” of the paintings that have come to exist in the world: