Around this time two years ago in February, I was struck with horrendous news from my aunt Luba of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. My aunt, whose family and home were located in Slovyansk, Ukraine, had been situated in the Donbas region—a sector that has since witnessed irreversible damage due to the invasion.

Every post-Soviet person can attest to the lingering stench of sorrow riddled with scrutiny. It is shared collectively across our upbringings. In plain terms: this kind of mourning has been trodden out by the generations who survived and/or escaped the USSR and its subsequent collapse. Every child can recall dozens of personal or traveled stories that describe migration, loss, the inhumane offenses traversed across their homelands, death—or a national grief, that is continuously evidenced by authoritative regimes, still metastasizing in post-Soviet nations even today. Grief is a kind of haunting, a loose screw, and it is always loosened at its own accord.

It was in March, that Atahan, my then boyfriend of one year, sat pensively with me in the bedroom of a Montreal Airbnb. We were on call to evacuate my aunt, her husband, and four children. They had started shelling her neighborhood. The blasts reverberated through the walls of their underground bunker. Without meditating too intensely on the details of sheer terror shared in the vital hours that followed, each shell was a “horrific shock that crawled across the body, peeling your skin up from off of your bones”.

Some sense of time had eventually passed, but it passed gruelingly, lessening the immense grief I felt for their material losses and inability to return. In May of 2022, I had packed a suitcase alongside two spilling boxes of art materials, shipping them to Norfolk, CT, where I would go on to spend the next two months. Then there was the matter of figuring out how exactly I was going to “make artwork” for a prestigious fellowship that expected intensive art-making from its candidates.

How in the world could I even justify “intentional making” amidst all that was going on? The expectations of this academically generous but isolating environment felt all too untimely to process. How do artists insist on making especially in the circumstance of on-going grief, in the circumstance of war? Although I was ultimately unable to produce works that meaningfully fueled or transformed my practice during my time there, I have since arrived at some understanding of making in the sight of grief.

On January 14th this year, Atahan passed away in a tragic and unimaginable accident. Like a robbery in the night, I awoke to discover the news. A deafening stillness befell me when reading an article that listed his name and details of the accident.

Death is rarely slow.

It is irrefutable and asphalting. Grief however, is a kind of haunting. It is a meandering nuisance, demanding revision, your attention, a sinking plunge—because grief is never satiated by a half effort. It is a selfish child who screams and kicks until you have failed and succumb to its indulgence. The week following Atahan’s death was perhaps the hardest. The loss of appetite, and the insistence from the outside world to move forward. I fought and refused time—I could not compromise with the idea of having to once again return to a world flexing and changing by the millisecond, all moving forward without him. It felt akin to those first few days when I had received that horrific message about the invasion, but this time it was even closer.

During my final weeks at the Yale residency, I remember calling Atahan to confess how ineffectively I felt I had spent my time. That the last two months felt like a limbo of working on something for the sake of working on something—or much worse, an impossible battle of trying to arrive at the simple act of making. I was so hurt that I was unable to discover the precious secrets and findings I had so desperately hoped for in this experience. That the promise of sanctioned making or isolation, did not ultimately propel me into what I had been waiting for.

When we are grieving, we are waiting on an image. We are waiting for some fantastical picture to explode into view, to clasp tight into focus, where familiar scents, sounds and commotion can pour up and out from. The reason why I could not paint happened to also be the only reason I could manage to in the weeks following after his death. The greatest impossibility of being a painter is that one is always left with the tremendous task of imagining a new image. In order to transcribe new images, lifelines, sequences, worlds, and visions into existence, we must acknowledge a time and station beyond the present. In choosing to paint and invent new images, we are surrendering to a future, to futures—which subsequently means loosening our grip on the past.

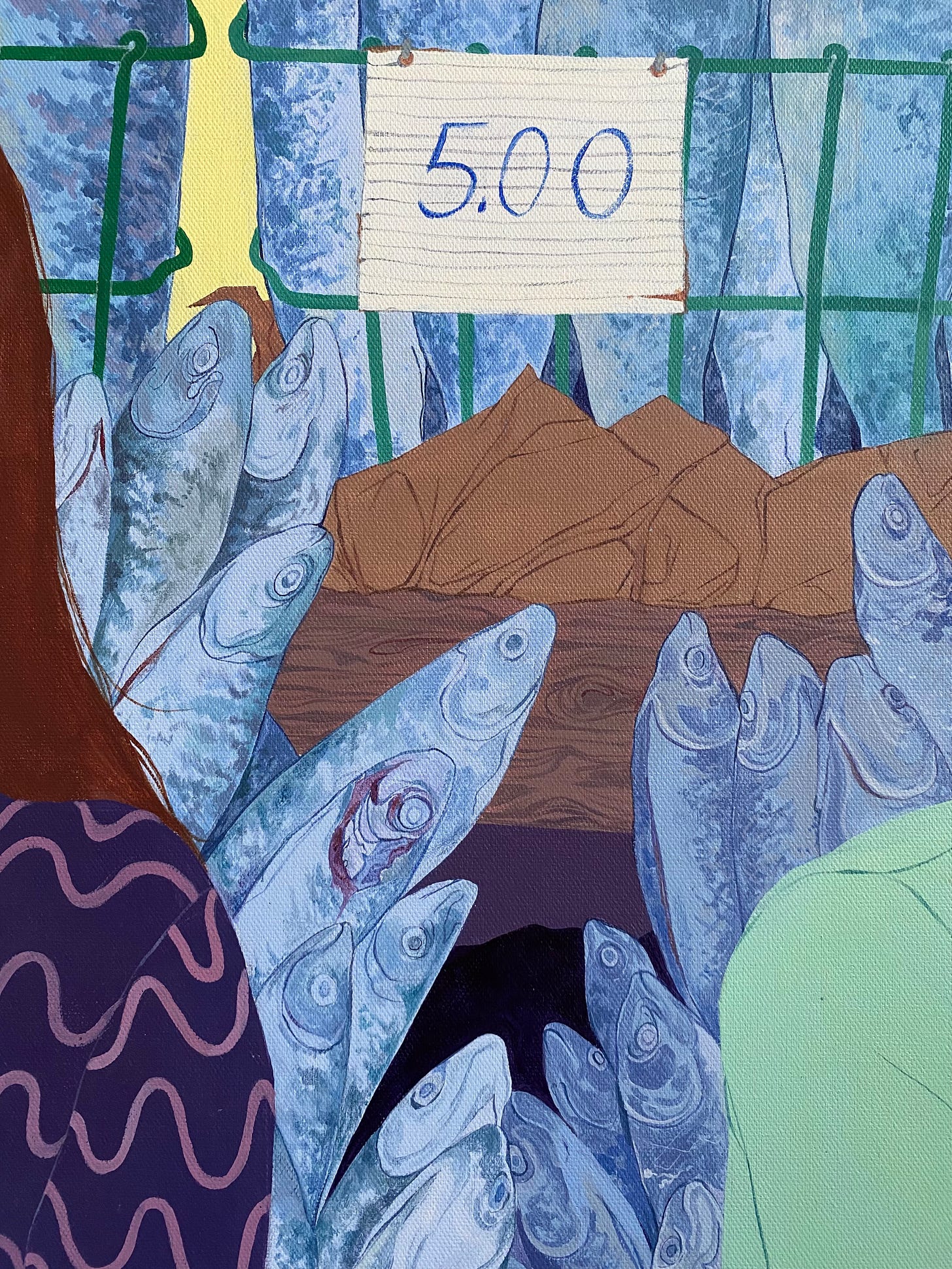

This meant submitting to a future that could only reach softly towards the lifelines still present in my world now. When painting, every brush stroke is a one-way full speed highway, and at some point we must decide on a finish line, to take the exit out. The images we paint are irrefutably locked into a dimension of time and space that can only begin and end with every applied brush stroke. A ritualistic transference of stories from soul to surface.

We are left finally only to walk forth through grief. I am here today still carrying these grievances. My aunt and her family have escaped the barrage of Russian violence and shuttering shells, at least for the foreseeable future…but they too carry their own grief.

The future is definite and forthcoming—and although its shape is scathingly revealed only through grief, an afterwards is always promised.